Hajiya Balaraba Ramat Yakubu, December 2012 (c) Carmen McCain

Last month, Abuja-based Cassava Republic Press contacted me and asked if I would contribute a “book of the month” for their monthly book series. I am currently working on a dissertation chapter on three of Balaraba Ramat Yakubu’s novels: Wa Zai Auri Jahila?, Wane Kare ne ba Bare ba?, and Alhaki Kuykuyo Ne (translated by Aliyu Kamal as Sin is a Puppy… ). So, I identified the “Book of the Month” as Wa Zai Auri Jahila? (Who will marry an illiterate woman?), Hajiya Balaraba’s novel about the irrepressible Abu who is forced into marriage at 13 but refuses to let her early trauma at the hands of her 52-year-old husband define her life. I sneaked in a brief summary of the other novels as well. You can read the post here on the Cassava Republic Press blog.[Update, the link is broken on the Cassava Republic Press blog, so I have archived it on my own blog here. -CM, 1 August 2015]

“Wa Zai Auri Jahila?” Balaraba Ramat Yakubu’s novel on child marriage, reviewed by Carmen McCain

In July, I also wrote a longer review of Wa Zai Auri Jahila? in my column, which I will copy below. The scholars Abdalla Uba Adamu [see here and here], Novian Whitsitt [see here and here], and Graham Furniss [briefly, see here] have also written about the novel:

The question of child marriage and Balaraba Ramat Yakubu’s novel Wa Zai Auri Jahila?

- Category: My thoughts exactly

- Published on Saturday, 27 July 2013 06:00

- Written by Carmen McCain

Last week, after I asked “Where are the translations?”, I was delighted to hear from two professors working on Hausa-English translation projects: Professor Yusuf Adamu and Professor Ibrahim Malumfashi.

I continued to think about the issue of making Hausa literature available to a wider audience this week as I read Hajiya Balaraba Ramat Yakubu’s two part Hausa novel Wa Zai Auri Jahila?/ Who will marry an Ignorant Woman?, first published in 1990. The novel is an important contribution to the ongoing debate about child marriage in Nigeria, and it made me think that if I were to translate a novel, I would love to translate this one. For those who read Hausa, the novel is currently no longer in the market, but Hajiya Balaraba tells me she soon plans to release a new edition in one volume of around 400 pages.

The novel, set mostly between the village of Gamaji and the city of Kano, with brief detours to London, Kaduna, and Lagos, tells the story of the headstrong, bookish girl Zainab, nicknamed Abu by her family. In the first part of the novel, Abu’s dreams are threatened by the pride and thoughtlessness of men. When she is thirteen, Abu’s father, Malam Garba, swayed by other villagers who think Abu is too old to be outside the house, pulls her out of school. Amadu, her cousin who had promised from childhood to marry her, forgets his proclamations of love when he leaves the village and goes to Kano to start university. Starting an affair with an older and more educated woman, he refuses to marry Abu—telling her he cannot marry an uneducated woman. Malam Garba, humiliated by Amadu’s rejection of his daughter on the eve of their marriage, insists that Abu must marry anyway and gives her to the first suitor to come along, Sarkin Noma. Her marriage is more about his pride than her well-being. Ignoring her tears, he maintains she will be happy once she is in her husband’s house. It is not until after the marriage that Malam Garba regrets the ridiculous husband to whom he has given his thirteen year old daughter: a fifty-two year man, with a big stomach and red eyes, whose own eldest daughter is four years older than Abu. Sarkin Noma’s insistence on marriage to Abu comes initially out of his own need to reinstate control over his three quarrelsome wives and later out of his desire to subdue the stubborn Abu, who expresses her disgust for him every time he comes courting. His pursuit becomes a horrifying exercise in asserting his power. He tells her “No matter how much you refuse me, I will marry you.” For those who do not believe marital rape is possible or who believe the best place for a young girl is in her husband’s house, this disturbing novel should cause them to reexamine their assumptions.

As against the sort of arguments I’ve seen this week that girls will become wayward if they are not married young, Wa Zai Auri Jahila? provides a different and much needed voice—the perspective of a girl herself. Balaraba Ramat Yakubu has spoken in interviews about how she herself was married as a very young girl to a man much older than her, and her portrayal of Abu’s suffering and determination to succeed rings true. She resists the temptation to caricature Abu’s antagonists as simple evil villains, however. Abu’s father, despite his pride, comes to regret what he has done to his daughter. Even Sarkin Noma who violently forces himself on his young bride dwindles to a pathetic character, shocked by the secrets his wives have kept from him, and frittering away his life longing for a woman he cannot have. The novel does not demonize particular characters so much as show how a patriarchal culture traps and degrades even those men whom it supposedly benefits.

Though Abu is victimized by men as a child, she refuses to stay a victim. Haunted by Amadu’s harsh words about her lack of education, she determines to better herself. She is fortunate to have an aunt in Kano who supports her in her quest for education, and the village girl Amadu rejected for her “ignorance” proves her brilliance once she enrolls in remedial classes. As Abu grows in years, knowledge, and maturity, changing her name from Abu to Zainab, her old antagonist Sarkin Noma dwindles into a pitiful creature. It is as if her success emasculates him. Indeed “…almost everyone knew that Sarkin Noma was no longer a man.” Yet, Zainab’s education is a blessing to almost everyone else, including the other men in her life. Though she makes Amadu suffer when he comes back from schooling in England, he comes to realize how badly he had treated her. Similarly she is able to influence her father so that her sister is not married at a young age as she was but instead allowed to go to secondary school. The title is ultimately ironic, as over the course of the novel the power shifts to create a more equal relationship between men and women. The question becomes not “Who will marry an ignorant woman,” but who is worthy to marry an educated one?

For all the horror of part one, part two is full of sweetness. As I read the last one hundred pages I had a huge smile on my face. There are several love stories here, but the most tender ones are between old married couples. I was touched by the scene where Abu’s parents, Malam Garba and Bengyel, make up after a long quarrel, with Malam Garba humbly apologizing to his wife. The endearments between Zainab’s aunt Hajiya Kumatu and her husband Malam Sango, married for twenty-three years despite their childlessness, brought tears

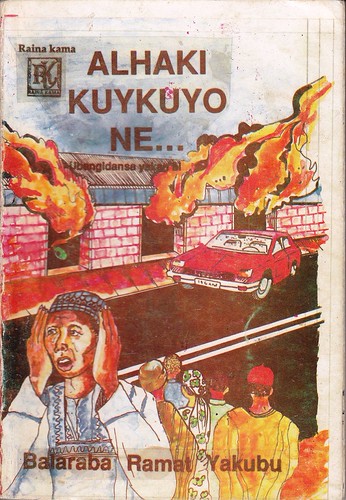

Hajiya Balaraba’s 1990 novel Alhaki Kuykuyo Ne.

to my eyes. As with Hajiya Balaraba’s novel Alhaki Kuykuyo Ne, the happiest moments here occur in households where there is one man and one wife.

In addition to demonstrating the attractiveness of love between one man and one woman, this novel provides a contextual lens through which to view the issue of child marriage. First, as Hajiya Balaraba notes in the introduction to the second part of the novel, the book serves as a warning to parents who force their daughters into marriage, and particularly illustrates the horrors faced by a thirteen year old given to a 52 year old man. Abu would have been much better off had Amadu, who was only four or five years older than her, married her as originally planned. Yet, even that marriage, the author implies, would have had its problems. In his teenage years, Amadu was immature, made the wrong friends, and chased the wrong kinds of women. He was not at a stage where he could have provided a stable home for Abu. Similarly, marriage at 13 for Abu not only complicated her ability to continue her studies but also damaged her body. Although she had gone through puberty, she was not developed enough to give birth successfully, and her old husband’s rough treatment injured her badly. While not explicitly condemning young marriage in the novel, the author demonstrates the contrast between Abu’s marriage as a child and the much healthier marriage between more educated financially-independent characters in their twenties.

There were occasional moments in the novel that I wish were different. There are several small factual errors which could easily be fixed in the next edition, such as implying that Oxford University, which Amadu attends, is in the city of London. I wish that instead of pursuing nursing, Zainab had gone all the way and become a doctor. I also wish that the unfaithful woman for whom Amadu left Abu was not portrayed as a Christian Yoruba. That said, the author, elsewhere, does portray positive relationships with the “Other.” Amadu meets several kind British characters in England and his friendship with the British woman Jennifer ends up helping him redeem his past mistake. Similarly, in Hajiya Balaraba’s 2006 novel Matar Uba Jaraba, part of the story is set in Ibadan where the Hausa boy Aminu grows up with kind Yoruba neighbours and marries his childhood sweetheart Shola. Ultimately, despite these flaws, Wa Zai Auri Jahila? is an important novel, which gives voice and agency to the “girl-child” who is so often used as a pawn in ideological battles but rarely gets the chance to speak for herself. I just wish that everyone could read Hausa and enjoy as much as I have this novel that takes you from the depths of horror to the joyful heights of love.