The Etisalat Prize for Literature just announced its 2015 prize for African Literature at a ceremony in Victoria Island, Lagos. The winner of the £15,000 prize is Congolese novelist Fiston Mwanza Mujila for his novel Tram 83, originally written in French and published by Éditions Métailié, Paris in 2014, and translated from French to English by Roland Glasser for Deep Vellum Publishing, Dallas. I have not yet read the novel, but I picked it up at the most recent Modern Language Association Conference on the recommendation of Aaron Bady. So, it is going onto the top of my reading list.

Let’s use this space to celebrate, also, the translator Roland Glasser, who writes here about the process of translating the novel. Glasser watched the ceremony via live webcast (Etisalat, couldn’t you have brought the translator to the event as well? This makes me also wonder if the prize money will be split at all?)

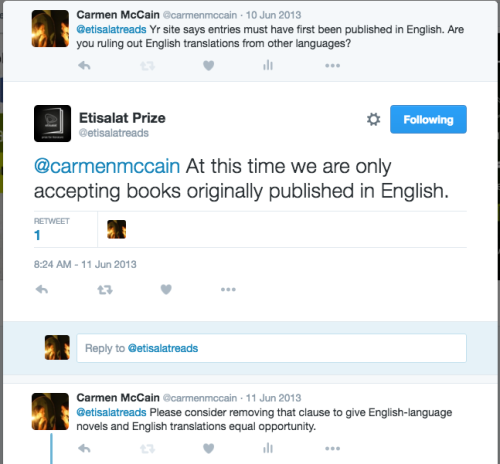

Tram 83‘s win is exciting on multiple levels, but I am the most excited about the reversal of Etisalat’s 2013 policy that the prize would only be given to works written originally in English. See the twitter conversation I had with the organization in June 2013.

I criticized the policy in my column in Weekly Trust, part of a two-week critique of African literary prizes inspired by my time at the 2013 Africa Writes event in London. Rather bizarrely the South African literary website Books Live, picked up on my critique of the Etisalat Prize and gave it a headline.

Since the time I wrote my critique, there have been many changes for the better. In 2015, Mukoma wa Ngugi and Lizzy Atree founded the Mabati-Cornell Kiswahili Prize for African Literature, In October 2013 Words Without Borders published a special issue on African women writing in indigenous languages, Abuja-based Cassava Republic/Ankara Press published a special Valentine’s Day anthology in 2015 featuring stories written in African languages translated by well-known authors, and Nairobi-based Jalada published a special language issue in 2015. Since 2015, Praxis Magazine has also been making an effort to publish creative work in African languages and in translation. There has been an upsurge of interest in Hausa literature, brought about by both the 2012 publication of Aliyu Kamal’s English language translation of Balaraba Ramat Yakubu’s novel Sin is a Puppy that Follows You Home by Indian publisher Blaft, and Glenna Gordon’s 2015 book of photography Diagram of the Heart that features gorgeous images of Hausa novelists. And now the Etisalat Prize for African Literature has become truly pan-African in awarding a Francophone novel translated into English, not from London but from Lagos. (The prize is in pounds rather than naira, but I suppose we have to take one thing at a time.) I hope the next big news will be that a pan-African prize is awarded to a novel translated from an African language.

In the meantime, I have realized I have not archived either one of my 2013 articles on the Africa Writes event or the Etisalat prize on this blog, so I will copy them below here:

Defining the “African story” in London: a preliminary response to the African Writes Festival at the British Library

- Category: My thoughts exactly

- Published on Saturday, 13 July 2013 06:00

- Written by Carmen McCain

It was around 10:20pm on 8 July in London. Just as I was handing my boarding pass to the ticket agent at Heathrow airport, I refreshed my phone screen and saw the news that Nigerian-American Tope Folarin had won the Caine Prize for African Writing for his story “Miracle,” a subtle well-crafted story set in a Nigerian church in the American state of Texas.

I had spent the weekend at the Africa Writes Festival hosted at the British Library in London, hanging out with the lovely Tope Folarin, as well as my two friends Elnathan John and Abubakar Adam Ibrahim, who had also been shortlisted for the prize. After finding my window seat and chatting a moment with my seatmate in Hausa, I asked her “have you followed the Caine Prize at all?” “Not really,” she said. “I’ve been so upset about the killing of these school children in Yobe.”

My heart dropped. As I kept refreshing the twitter homepage on my phone, waiting for the winner of the Caine Prize to be announced, I had seen some chatter on twitter about a school attack. I suddenly remembered the Facebook message my cousin had sent me a few days before condoling me on the school attack and saying she was praying for Nigeria. I hadn’t known what she was talking about, and I didn’t google the news. I was too busy going to the festival and seeing London-based friends, too sleep deprived from late nights of gadding about with writers. I did not read the full story of the attacks in which, according to Leadership, forty-two students and teachers at a Yobe boarding school were shot in their beds Saturday morning by invaders, until I arrived back in Nigeria on Tuesday morning.The juxtaposition of the two news items made me think about the ongoing debate about the Caine Prize and “stereotypes” about Africa. Last year in my article “The Caine Prize, the Tragic Continent, and the Politics of the Happy African Story,” I questioned the rhetoric of last year’s chair of the prize, British-Nigerian novelist Bernadine Evaristo, who said it is time “to move on” past stories of suffering in Africa. At the Africa Writes festival on a panel “African Literature Prizes and the Economy of Prestige,” on 6 July, Evaristo continued in this vein, speaking about how during her tenure with the prize, “I was absolutely determined that we were not going to have any traumatized children winning this prize.” She described her “battle” to make sure one particular story, “which ticked all the boxes … a boy living in a terrible situation, prey to gangs, brutalized etc” did not make the shortlist. In her defense, she brought up U.S.-based author Helon Habila’s recent review of Zimbabwean novelist NoViolet Bulawayo’s novel We Need New Names, in which he commented that it seems Bulawayo “had a checklist made from the morning’s news on Africa.” Habila, himself a recipient of the 2001 Caine prize for his story about the suffering of a journalist in a Nigerian prison, worried that a certain “Caine Prize aesthetic” was developing that valued sensational stories of Africa—what he called “poverty porn.”

Ironically, Evaristo was expressing her impatience with stories about “traumatized children” only hours after the attacks on the school in Yobe. When I arrived back in Nigeria, a friend described to me a story he/she wanted to publish about terrorism in a Nigerian newspaper but was afraid of becoming a target. As I wrote in my article last year, “To say we must ‘move on’ past stories of hardship suggests to those who are suffering that their stories don’t matter—that such stories are no longer fashionable. Writers who live amidst suffering are in the unfortunate position of inhabiting an inconvenient stereotype. They are silenced by threats of terrorists inside the country and by the disapproval of cosmopolitan sophisticates outside.”

Later that night after Evaristo’s panel, Kenyan writer Mukoma wa Ngugi on the platform with his father, Ngugi wa Thiong’o, spoke of his concern about “this push for what I call Afro-Optimist writing … wanting to show an Africa that is very Hakuna Matata…. In Kenya you have a very, very wealthy estate and next to it you have poverty…. I think it is our job as writers to explore this contradiction.” In response to Habila’s essay he cautioned, “we have to be very, very careful. It’s too easy to say there is a Caine Prize aesthetic… it’s as if we want to paint happy colours over the poverty and all those complications.” Caine Prize nominee Chinelo Okparanta further argued that “many people who jump on the poverty porn thing don’t even understand the context of what is being said…. These are superficial discussions.”

When I asked Evaristo about these contradictions, she hurriedly assured me that she was not in the position to tell people what stories to write, but that it was time to “start talking about different kinds of stories coming out of Africa, and I think this is happening especially with Taiye Selasi’s new book, and Chimamanda’s new book…” Ironically, the two novels she cites as more exciting new African stories are about relatively privileged Africans living in Diaspora—stories more like her own than the stories of traumatized children she is so determined to squelch.

As I point out these contradictions, I do so self-consciously, because I recognize myself in Evaristo’s impatience, in my own tendencies to review books published abroad before those published at home. I too am implicated because in London, I too did not make the effort to follow up on my cousin’s mention of the school attack. Another shooting? I thought. It has become too common. I don’t want to know about it right now. I just want to enjoy all of these great debates about African literature.

It is perhaps for this reason precisely why it is so problematic to have the “gatekeepers” of what stories are heard centred in London or New York. Because even a writer like Helon Habila, who has written such beautiful novels about the humanity of Nigerians who laugh and love and write amidst conflict and poverty, now, from his professorial position in the West, jumps on the band wagon of complaining about how Africa is perceived in the rest of the world. But should not the focus, as Ngugi wa Thiong’o has long stressed in books like Moving the Centre, be instead on one’s immediate audience, expanding beyond that only when the story has been first heard at home?

Satirist and Caine Prize nominee, Elnathan John mentioned on several occasions during various interviews that he was still trying to get used to this talk of the “African writer” or the “African story.” He was writing, he explained, about northern Nigeria. His nominated story “Bayan Layi” was a northern Nigerian story, which he wrote shortly after the election violence of 2011, in which he was thinking about how to explain the nuance and complexity of the event to a Nigerian audience. Author of The Spider King’s Daughter, Chibundu Onuzo touched the heart of the problem when she challenged Evaristo’s assumption that such stories were meant for publication in Britain. “Why do African writers need to be published here?” Shouldn’t the focus, she asked, be on building up publishing institutions in Africa, so that editors and publishers on the continent make the decisions on what kinds of stories are the most important and export them, rather than always having the most famous African writers be those first recognized in the West?This, indeed, is one of the most central problems in discussions of African literature based in the capitals of what literary critic Pascale Casanova calls the “World republic of Letters.” Only rarely was there mention of the irony of such a festival being held at the centre of the former colonial empire, and there was more talk of “development” of African writers by Diaspora-based writers than I was comfortable with. However, I did think it was encouraging that Abubakar Adam Ibrahim’s “The Whispering Trees,” from his short story collection of that name, made the Caine Prize list. The Whispering Trees was the first title published by exciting new Nigerian publisher Parresia, and the story selected by the Africa-based “Writivism” Facebook group as their Caine Prize winner. As Africans continue to tweet, blog, sell books through homegrown digital distribution like the phone-based okada books, and develop their own prizes, there is hope that the “centre” will move south to the continent itself.

African Literary Prizes: Where are the translations?

- Category: My thoughts exactly

- Published on Saturday, 20 July 2013 06:00

- Written by Carmen McCain

Last week, in my discussion of the Africa Writes Festival, which was held on the 5-7 July in London at the British library, I followed Kenyan author and language activist Ngugi wa Thiong’o in calling for “moving the centre” of the discussion about African literature to Africa itself.

As fantastic an initiative as the festival in London is and as impressive as the Caine Prize, the Commonwealth prize, the Brunel Prize for Poetry, the recently announced Moreland Writing Scholarship, and other such initiatives to reward African literature are (may they flourish), the healthiest state of African literature will be when the infrastructure to support African literature is developed and hosted on the continent itself. As Caine Prize shortlisted writer Elnathan John pointed out at one of the first Caine Prize events in London on 4 July, “I think it is a shame that we are in London having this. I think all of us should be in Nairobi or Ghana or Lagos… Is the Caine Prize useful? Of course. It is among the best things that has helped African writing. But could the interaction be more equal? Yes. You don’t want us to just sit down be getting. We also want to interact and add value to the entire process, and I hope that as time goes by we are able to contribute more to that process.”

There are changes in this direction. Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and Helon Habila both regularly hold workshops in Nigeria funded by Nigerian banks. The Kenya-based (albeit with European and American sponsors) Kwani Manuscript Project just awarded its first three authors and plans to publish other submissions from its short and long list. The Ghanaian-based Golden Baobab prize, founded in 2008, awards and helps publish African children’s book manuscripts. The Nigeria-based Wole Soyinka Prize for Literature, founded in 2006, is awarded every two years to a work of African literature, cycling through a different genre each time. The NLNG Prize, though open only to Nigerians, similarly cycles through different genres and at a whopping $100,000 is one of the most financially rewarding African literary awards. The most recent Africa-based prize is the £15,000 Etisalat Prize for African literature that was founded in June 2013 to award first novels. Similar to the Wole Soyinka Prize in its pan-African scope, the Etisalat prize, which has its first submission deadline 30 August 2013, seems to go beyond some of the other prizes in infrastructure building. Its website mentions that “Entries by non-African based publishers will require a co-publisher partnership with an African based publisher should any entries be shortlisted,” and Etisalat commits to purchasing “1000 copies of all shortlisted books which will be donated to various schools, book clubs and libraries across the African continent.” Although the prize still looks north in offering the winner a U.K.-based fellowship at the University of East Anglia (and mentorship by British author Giles Foden) (why not a residency in an African location with an African writer?), the infrastructure building for African publishers is important. The most glaring deficiency to the prize, however, is this: Although the United Arab Emirates-based company Etisalat also gives a prize for Arabic children’s literature, the criteria for entry in the African Literature prize specifies that books are only eligible if they have FIRST been published in English. Now, the other prizes I’ve mentioned also specify English-language submissions but most also accept translations into English from other languages. Yet when I tweeted the Etisalat Prize’s twitter handle asking them if they were indeed excluding translations, they confirmed, “At this time we are only accepting books originally published in English.” Ironically in the photos of the Lagos gala event opening the prize, there were photos of steps honouring African writers Naguib Mahfouz, who wrote in Arabic, Okot p’Bitek who wrote in Acholi, Assia Djebar who writes in French, and Mia Cuoto who writes in Portuguese, all of whom are accessible to English-speakers only through translation.

This dismissal of translation, particularly from African languages, by those who desire to promote African literature is a shame, considering that translation has been the major way “world literature” is transmitted and studied between cultures. In Germany, the “International Literary Prize” awards the best German-translation of an international work, which was won this year by Christine Richter-Nilssons translation of Teju Cole’s novel Open City. The Nobel Prize has been given to writers of dozens of different languages including small ones like Danish, Icelandic, Norwegian, Japanese, Polish, Serbo-Croatian, Swedish, and Turkish. Yet translations from and between African languages are rarely rewarded or recognized even by Africa-based prizes.

It was this sort of exclusion that Ngugi wa Thiong’o challenged at the “Africa Writes festival” in London two weeks ago. During the 6 July panel discussion “African Literature Prizes and the Economy of Prestige,” he asked rhetorically, “Can you seriously think about giving a prize to promote a French writer but you put a condition that they write in Gikuyu?” He was concerned that “the abnormal has become normalized” when African languages, incredibly still called “tribal” languages by some festival attendees, become almost invisible in discussions of African literature.

Obviously, as Bernadine Evaristo, founder of the Brunel Prize for African poetry pointed out, there are logistical problems with prizes that accept entries in multiple languages, such as finding jury members who can adequately judge in submissions. While there are fewer such logistical problems with translations, Billy Kahora of Kwani and Caine Prize administrator Lizzy Attree pointed out that submissions in translation are rare.

In a later appearance, Ngugi spoke passionately of his “deep concern at what we are doing to the continent and this generation.” “It pains me, in a personal kind of way to see the entire intellectual production of Africa—the one that is visible—in European languages” as if “Africa can only know itself—be visible—in English.” While qualifying that he did not begrudge anyone their prizes, he repeated his call for translation, not just between African and European languages, but between African languages themselves. He pointed out that people should focus on whatever language they inherited and then learn others. “Why don’t we secure our base economically, politically, linguistically and then CONNECT with others. […] If you know the language of your community and then add all the languages of the world to it, that is empowerment.”

It is not as if literature in African languages does not exist or even flourish. The day before, Ghirmai Negash, Mohammed Bakari, and Wangui wa Goro spoke of translating into English, Gikuyu, and Swahili Gebreyesus Hailu’s Tigrinya-language novel The Conscript written in 1927 about the experiences of Eritrean men conscripted by Italy to fight in Libya. In Nigeria, there have been novels and poetry written in Efik, Hausa, Igbo, Tiv, Yoruba, and other languages. In Hausa alone, there are thousands of published novels and a voracious reading public. Though it seems to have been stagnant for a few years, there have been three editions of the Engineer Mohammed Bashir Karaye Prize for Hausa Writing, which awards Hausa prose and drama. Yet, as far as I know, not one of these award-winning or nominated works has been translated into any other language, and judging from the lack of interest in translation at the level of “African literature” it is unlikely that they will be without the intervention of bodies interested in supporting translation.

Fortunately, there are some venues interested in publishing translated work. Last year, the Indian publisher Blaft published Balaraba Ramat Yakubu’s Hausa novel Alhaki Kuykuyo Ne translated into English as Sin is a Puppy… by Aliyu Kamal and are interested in other such translations. The translation journal Words without Borders recently contacted me looking for African women’s writing translated from African languages. The problem is that there are few literary translators, and even fewer financial incentives within the continent.

Now, one solution is to protest this purposeful exclusion of translation by the Etisalat Prize, which you can do by tweeting them at @etisalatreads or emailing them at contact@etisalatprize.com. But judging from the experience of prizes like the Caine, even if Etisalat changed the rules, would there actually be any translations submitted? Another, perhaps more practical solution is to work on building up resources and training for translators through existing structures, like the Ebedi Writers Residency or to start new residencies to for writers and translators to come together to work on projects. Another incentive would be to start a prize for African literature in translation to focus on making the wealth of literature in Africa languages available to the world. Any lovers of literature out there who want to help make this happen?

As Ngugi said, this is his challenge to the next generation, “Connect. Let us choose the path of empowerment.”