The topic of renewable energy, as an environmentally friendly option, has always interested me, even as a young child, but I think growing up in Nigeria, where the power supply is unstable, made me even more passionate about the topic. Renewable energy is more than just a way to be “green;” it is a way to survive, and I am shamelessly evangelistic in my promotion of renewable energy as the best option for Nigeria. We have some of the best sun in the world, as well as excellent wind and hydro resources. We could also do very well with (my current favourite option) gasification of organic waste products. In fact, a family friend who works in renewable energy told me that agricultural factories could basically run themselves and staff housing on the energy produced from waste materials such as husks and corn stalks. Estates could potentially go grid-free as well as enjoying a tidy environment by gasifying their trash or sewer systems.

After spending nearly two and a half years suffering the vagaries of NEPA and refusing, out of principle (and also, I admit, fear) to get a generator, I finally invested in an inverter and battery system. Until a few minutes ago when NEPA came back on, I was working on a power supply from my battery system, without which I would not be able to do my work. The battery charges when I have electricity and supplies me with power to run my laptop, inkjet printer, tv, dvd player, and DSTV device, as well as recharge phones and recharge a battery lamp and phone (You would need a much larger battery and inverter system to run a refrigerator, heating element, or airconditioner). My battery needs about three hours of electricity for a full charge, and when fully charged can provide up to 10 hours of electricity. I use mine very lightly, unplugging printer and TV when not in use, and turning it off when I sleep or go out, and since I purchased it in around February, I have not had my battery run out even once. Although the initial investment is pricier than a generator, it is completely worth it to me. There is very little noise (just a light hum), no unpleasant fumes, and no having to go out and waste time in queues for petrol or having to handle petrol. I bought my system from the Indian company Su-Kam on Ibrahim Taiwo Road, but there are also other suppliers in Kano, such as Dahiru Solar Technical Services Ltd (which built the solar-tracking system for the German cultural liason, Goethe Institut, Kano office) on Zaria Road. My goal, once I am done with my PhD and actually earning a reasonable income (!) is to someday invest in solar and be free of NEPA altogether.

Therefore, I am particularly excited about a lecture and exhibition on renewable energy that is opening today at the Goethe Institut-Nigeria, Kano liason office, co-sponsored by the General-Consulate of Germany in Lagos and the Delegation of German Industry and Commerce in Nigeria. I wanted to get this up a bit sooner, but have been insane with writing deadlines. For those in Kano, seeing this before 2pm, Thursday, there will be a lecture at that time on renewable energy, given by Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Palz, the Chairman of the World Council Renewable Energy.

Venue: Goethe Institut Nigeria, Kano Liason Office, 21 Sokoto Road, Nassarawa GRA, Kano.

Time: 2pm, Thursday, 30 June 2011

The lecture will open a one week exhibition at the Goethe Institut, Kano on “Renewables-Made in Germany” on “renewable energy sources, technologies and systems,” which has recently been on display at the Goethe, Institut, Lagos. On July 11-15 it will move to Abuja and be displayed at the Hilton Hotel. The exhibition is open from 30 July to 7 July, 10am to 5pm and entrance is free.

The exhibition features German renewable energy technology and “answers questions such as:

What are the advantages of the different renewable energy sources and technologies?

How do the different type of renewable energy technologies work?

Under what conditions can these technologies be used?

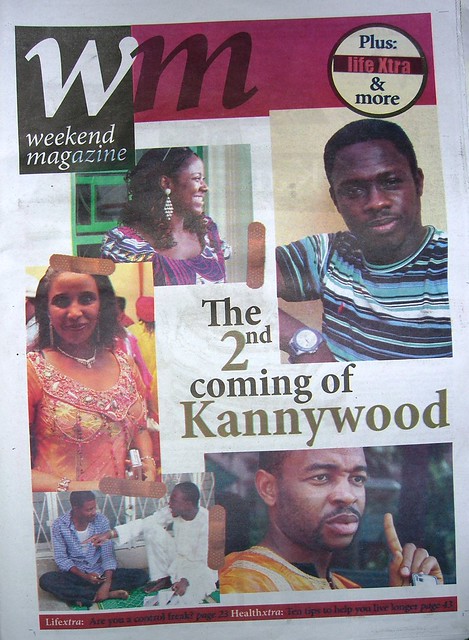

The Goethe Institut, Kano, is a particularly appropriate venue to hold the exhibition since the Goethe Institut, which is housed in the old Gidan bi Minsta, parts of which were built back in the 16th century, is the first building in Kano state, and the third in the nation, to be powered by a solar tracking system, a mechanized system which follows the sun for optimum solar power absorption. Although I am generally a bit suspicious of agendas of cultural agencies, I have been very impressed with the Goethe Institut’s programming and support of Kannywood, and have written about it elsewhere in my column.

A few weeks ago I interviewed Frank Roger, the director of the Kano liason office for Goethe-Institut, Nigeria, about the solar energy project he initiated. Click on the photo below to read in hard copy, or scroll below the photo for the text.

In Kano, Goethe Institut goes off-grid with solar power

When I visited Germany a few years ago, one of the things that most impressed me was that nation’s visible commitment to renewable energy sources. Driving through the countryside, I saw windmills to capture and convert the wind into energy; neighborhoods full of “passive houses” built and insulated to need very little energy for heating during the cold winter season; and solar panels for conversion of sunlight into electricity on many houses. Why aren’t we doing more of this in Nigeria? I thought. Nigeria is much more blessed with sun than Germany and much more in need of alternate electricity sources. I was particularly excited when I heard that the Goethe-Institut, the German cultural centre established in Kano in 2008, had gone “off-grid” and was now run completely on solar power. In April when the Goethe-Institut hosted the one-day Kannywood FESPACO symposium, the lights were on, the computers were running in the offices. The sound speakers and the digital projector worked without a blink. There was no noisy generator filling the compound with fumes, just a large mechanized frame of solar panels to capture the sun.

I asked Frank Roger, the director of the Goethe-Institute, Kano, about their energy supply, and I’ve included parts of our conversation below. He gave me a little background about German energy politics, the Goethe-Institut, and their solar energy project, highlighting the wisdom of traditional architecture and the great possibilities of solar power to transform the way electricity is experienced in Nigeria and the world. The Goethe-Institut, which has been in Lagos since 1962, focuses on “intercultural exchange and the promotion of various fields of the arts.” When they established a liason office in Kano in 2008, they were invited by the Kano State History and Culture Bureau to move into the old adobe Gidan bi Minista building, the upper floor of which was constructed in 1909. The History and Culture Bureau believes that “the basic structure of the ground floor has been around since the 16th century. It was [first] used by title holders of the emir. In 1903 when the British came to Kano, the first British minister, who was called Frederick bi Minista, resided here. He established the first arts and crafts school in Kano here, so this building has a real history of cultural activities. Later on MOPPAN [Motion Picture Practitioners Association of Nigeria] offices were here, then the copyright commission. When I came in 2008, the house was basically not used.”

“The Goethe-Institut does not pay rent but maintains the building. We renovated the whole building, the plastering, you have to do quite often, checking it after rainy season. We reconnected water supply and put on a new roof, but there was still the problem of energy supply. Even though this is not far from the government house, still the [electric] supply was very unreliable.

“The easiest way would be to buy a generator and just do it that way. But then the idea [of solar power] came up. There’s one thing about this building and the architecture. It has natural ventilation. It’s quite cool inside so you don’t really need air conditioning. Even though it’s April, it’s very comfortable inside. If you have these modern concrete buildings, you definitely need air conditioning for an office, and then it’s a bit costly when it comes to solar power. If you want to invest in solar, you first have to do a power load survey. You have to know how much you need for consumption, and according to that, then solar company will design you the system you need. That’s why you cannot just say in general what is the size or cost of a solar power system. It is individually designed according to your needs. So the idea was instead of following this generator mainstream that we look for an alternative, and since solar has a big boom in Germany, we said ‘why not?’ Kano is much more exposed to the sun than our belt in Germany with its bad weather and short days in winter. In Kano you have hours of daily sunlight. In August in the rainy season, you can expect 5-6 hours. And in March-April, up to 11 hours of sunlight, so it’s really obvious to use it. The system we have was installed by Baba Dahiru [of Dahiru Solar Technical Services Ltd], a Kano businessman. And what he always says is that solar is free, and it is true. The energy from the sun comes for free, everyday newly. Of course, first you have quite high investment costs. If you want light at night, you also have to invest in batteries, which are not so cheap. But normally it pays off after about three years.

“We cancelled our NEPA account. Basically with our solar system, we run everything in this office now. We are off grid [disconnected from PHCN], and we have a fridge, our computers, the sound system, printer, copy machine, lights, lighting for exhibition, security lights at night that all run without any problem. We did the official opening in December, but had the test run since August, and it has run [from that time] without problems. You don’t really have maintenance costs. They come from time to time to make sure the screws are still tight. The lifespan of batteries is comparable to that of a generator, so after 6-7 years they have to be renewed. But the PV, photovoltaic panels [which capture the energy from the sun] run with 90% guarantee for 10-15 years, and at 80% rate of performance from 20-25 years, which is a really long term investment.

In addition to reliable electricity, using solar energy has other benefits. “There is no pollution. We don’t contribute to global warming now. There is no noise, which is important for our programmes. Here you feel it’s a little paradise because it’s so quiet and peaceful. We have installed solar panels not only as our energy supply system but also looked at it as an educational project to spread the idea of alternatives to the oil, coal gas, fossil fuels. Even though Nigeria is at an oil peak now, there will be a time when the oil worldwide will be finished. So, it is a good idea now while you have a lot of revenue from the oil industry to look ahead and invest in future technologies.”

“There’s a lot of investment in renewable energy in Germany now. Wind power is the first, also offshore wind power stations on the North Sea, even solar, though we have bad sunlight, also hydro power, some geotherm, and biological waste.”

After the Fukushima nuclear tragedy following the earthquakes and tsunami in Japan, “it was quite a big debate in Germany. We have something like 17 nuclear power plants in Germany. The majority want to get rid of this risky technology. The people in the renewable energy industry said by 2020 they will completely replace nuclear power in Germany with renewable resources, solar, hydropower. That is like nine years from now.”