Wednesday evening, April 27, 2011, Zoo Road in Kano, the street lined with Kannywood studios, exploded into celebration. Young men pulled dramatic stunts with motorbikes and shouted their congratulations to Hausa filmmakers. “Welcome back home, brothers. Welcome back from Kaduna,” directors Falalu Dorayi and Ahmad Biffa recall them saying. “We embrace you ‘Yan fim.’ We are together with you. We are happy that he has returned.”The win of PDP

Governor Rabi’u Musa Kwankwaso, incoming governor of Kano State, and also governor from 1999 to 2003 (Photo Credit: Nigerian Best Forum)

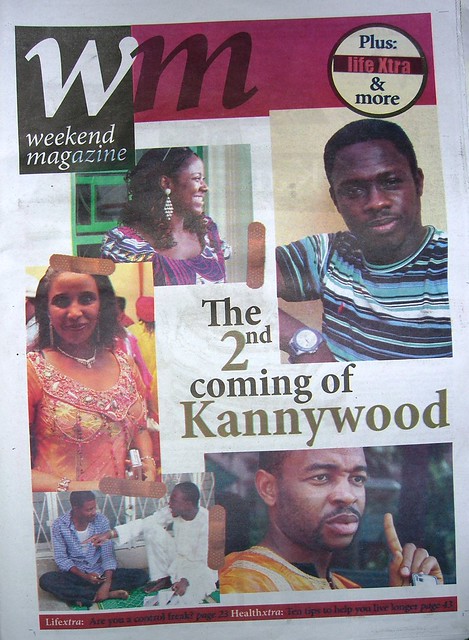

candidate Dr. Rabiu Musa Kwankwaso as governor of Kano, his second tenure after a four-year term from 1999-2003, had just been announced. INEC figures listed PDP as winning 46% of the vote with 1,108,345 votes, closely followed by Alhaji Salihu Sagir of ANPP with 43.5% of the vote with 1,048,317 votes. To anyone familiar with the Hausa film industry, which according to recent National Film and Video Censor’s Board figures makes up over 30% of the Nigerian film industry, this association of a political win with film was no surprise. Some of the most visible Hausa filmmakers have become increasingly politically active following a crackdown by the Kano State Censor’s Board, during which many practitioners and marketers of Hausa films had been fined, imprisoned, and harassed. While many of those associated with the film industry supported CPC and Buhari for president, the feeling among many filmmakers in Kano was that for governor any of the candidates would be better than ANPP. The two term ANPP governor and presidential candidate Ibrahim Shekarau, who had initially been passionately supported by

Former Governor Ibrahim Shekarau, governor of Kano State fro 2003-2011, and ANPP presidential candidate in 2011. (I took this photo during his trip to Madison, Wisconsin in 2007) (Photo credit: talatu-carmen)

at least some of Kano’s writers and artists, was now deeply disliked by most film practitioners, in part, for appointing Abubakar Rabo Abdulkarim former deputy commandant of the shari’a enforcement group hisbah as director general of the Kano State Censor’s Board. Malam Rabo, as he was known, regularly went onto the radio to denounce film practitioners for ostensible moral defects and had overseen a board which often arrested filmmakers.

After surveying candidates in the gubernatorial race for how they would support film, the Motion Pictures Practitioners Association of Nigeria (MOPPAN), as the association’s president Sani Muazu reported, publically campaigned for Kwankwaso. Movie star,

Comedian Klint de Drunk, with Kannywood stars Sani Danja and Baban Chinedu at an Abuja press conference for NAISOD, 2010. (c) Carmen McCain

producer, director, and musician Sani Danja, who founded Nigerian Artists in Support of Democracy (NAISOD), and comedians Rabilu Musa dan Ibro and Baban Chinedu were among those who lent their star power to the new governor’s campaign. This public support for PDP among some of the most visible film practitioners had put Kano based filmmakers in danger the week before. Angry about the announcement of PDP’s Goodluck Jonathan as winner of the presidential election, area boys hunted for Sani Danja, threatened other recognizable actors and vandalized studios and shops owned by Kannywood stakeholders. (For this reason, while some filmmakers have come out publicly in support of candidates, there are others who are reluctant to speak openly about politics. The Dandalin Finafinan Hausa on Facebook has banned discussion of politics on its wall, requesting members to focus on discussions of film.) By the next week, however, as Falalu Dorayi relates, the same area boys who had been hunting Sani Danja were now celebrating him.

Producer and makeup artist Tahir S. Tahir with Director Falalu Dorayi celebrating Kwankwaso’s win. April 2011 (c) Carmen McCain

While Governor-elect Rabiu Musa Kwankwaso was seen as the champion of the filmmakers during the 2011 election cycle, it was under Kwankwaso, who first served as governor of Kano from 1999-2003, that the first ban on Hausa films was announced and that the Kano State Censor’s Board was created. Abdulkareem Mohammad, the pioneering president of MOPPAN from 2000 to 2007, narrated how in December 2000, the Kano State Government pronounced a prohibition on the sale, production and exhibition of films in Kano state because of the introduction of sharia. MOPPAN organized and “assembled industry operators in associations like the Kano State Filmmakers association, Kano state artist’s guilds, the musicians and the cinema theatre owners, cassette sellers association” to petition the government to either allow them to continue making films or provide them with new livelihoods. It was the filmmakers themselves under MOPPAN who suggested a local state censorship board, which would ensure that film practitioners were able to continue their careers, while also allowing oversight to ensure that their films did not violate shari’a law. The censorship board was ultimately meant as a protection for the filmmakers to allow them to continue their work.

Outgoing President of MOPPAN, Sani Muazu points out that MOPPAN’s support of Kwankwaso was because he had promised re-establish the original intent for the censorship board, with a Kannywood stakeholder in the position as head of the Kano State Censorship Board, rather than an outsider who did not know the industry. Most Hausa filmmakers speak of the censorship board as a compromise between the film industry, the community and the government. Director Salisu T. Balarabe believes then Governor Kwankwaso was trying to follow the demands of those who voted for him, “If the government wants to have a good relationship with people it has to do what the people want.” Kannywood/Nollywood star Ali Nuhu said, “I won’t forget how in those three or four months [during the ban], they sat with our leaders at the time of Tijjani Ibrahim, Abdulkareem Muhammad, Hajiya Balaraba and the others. They reached a consensus, they understood the problems that they wanted us to fix and the plan they wanted us to follow.”

Nollywood/Kannywood star Ali Nuhu on set of Armala with Executive Producer Aisha Halilu. April 2011 (c) Carmen McCain

Although the censors board had banned several films, such as Aminu Bala’s 2004 cinema verite style film Bakar Ashana, which explored the moral complexities of the world of prostitution, and enforced rules on censorship

Aminu Bala’s film Bakar Ashana that was banned by the Kano State Censor’s Board in 2004.

before marketing, filmmakers for the most part did not seem to have major problems with censorship until August 2007, when a sex scandal broke out in Kannywood. A privately made phone video of sexual activity between the actress known as Maryam “Hiyana” and a non-film industry lover Usman Bobo was leaked and became one of the most popular downloads in Kano. Alarmed by what some were calling the “first Hausa blue film,” although the clip was a private affair and had nothing to do with other Hausa filmmakers, critics called for serious measures to be taken. A new executive secretary Abubakar Rabo Abdulkarim (his position soon

Maryam Hiyana, who was seen as a victim in the scandel, became an unlikely folk hero with stickers of her likeness on public transport all over Northern Nigeria. (c) Carmen McCain, 2008

inflated to the title of director general) was appointed by Governor Shekarau to head the Kano State Censor’s Board. He required each film practitioner to register individually with the board, an action he defended as being provided for in the original censorship law. Not long after Rabo was appointed, actor and musician Adam Zango was arrested and sentenced to three months in prison for releasing his music video album Bahaushiya without passing it through the Kano State Censor’s Board. He was the first in a series of Hausa filmmakers to spend time in prison. Former Kano state gubernatorial candidate and Kannywood director Hamisu Lamido Iyan-Tama was arrested in May 2008 on his return to Kano from Abuja’s Zuma Film Festival where his film Tsintsiya, an inter-ethnic/religious romance made to promote peace, had won best social issue film. He was accused of releasing the film in Kano without censorship board approval. Although Iyan-Tama served three months in prison, all charges were recently dropped against the filmmaker and his record cleared. Popular comedians dan Ibro and Lawal Kaura [both of whom are now late, see my memories of both Rabilu Musa and Lawal Kaura] also spent two months in prison after a hasty trial without a lawyer. Lawal Kaura claims that although they had insisted on their innocence, court workers advised them to plead guilty of having a production company not registered with the

FIM Magazine feature on Ibro’s time in prison, November 2008.

censorship board so that the judge “would have mercy” on them. These were only the most popular names. Others who made their livelihoods from the film industry, from editors to singers to marketers, spent the night in jail, paid large fines, and/or had their equipment seized by enforcers attached to the censorship board.

Although Governor Shekarau in a presidential debate organized by DSTV station NN24 had claimed that “the hisbah has nothing to do with censorship,” Director of Photography Felix Ebony of King Zuby International recounted how hisbah had come to a location he was working on and impounded four speakers and one camera, telling them they had not sought permission to shoot. Other filmmakers complained that there was confusion about under what jurisdiction arrests were being made. Although in a February 2009 interview with me, Rabo

Felix Ebony, director of photography with King Zuby International. (c) Carmen Mccain

also claimed that the censorship law was a “purely constitutional and literary law […] on the ground before the shari’a agitations,” the public perception seemed to be that the board was operating under shari’a law, perhaps because of Rabo’s frequent radio appearances where he spoke of the censorship board’s importance in protecting the religious and cultural mores of the society. Director Ahmad Bifa argued, “They were invoking shari’a, arresting under shari’a. If they caught us, we all knew, that they had never taken us to a shari’a court. They would take us to a mobile court […] But since it was being advertised that we were being caught for an offense against religion, we should be taken to a religious Islamic court, and let us be judged there not at a mobile court.”

The ‘Mobile’ Magistrate Court at the Kano Airport where Censorship Board Cases were tried. This photo was taken in July 2009 during the trial of popular singer Aminu Ala. (c) Carmen McCain

The mobile court Biffa referred to seemed to be attached to the censorship board and was presided over by Justice Mukhtar Ahmed at the Kano airport. After the Iyan-Tama case came under review, the Kano State attourney general found the judge’s ruling to be ““improper”, “incomplete”, a “mistake” and requiring a retrial before a more “competent magistrate.” Justice Ahmed was transferred to Wudil in August 2009; however, censorship cases continued to be taken to him. In January 2011, popular traditional musician Sani dan Indo was arrested and taken to Mukhtar Ahmad’s court, where he was given the option of a six month prison sentence or paying a fine of twenty-thousand naira. The decisions made by the board and the mobile court often seemed of ambiguous motivation. In 2009, Justice Mukhtar Ahmed banned “listening, sale, and circulation” of eleven Hausa songs, citing obscenity, but obscenity was rarely as easily identified as the cutting political critiques in them.

11 Songs banned by Justice Mukhtar Ahmed. (c) Alex Johnson

The effect of these actions was to relocate the centre of the Hausa film industry away from the flourishing Kano market, to Kaduna. Many filmmakers began to claim their rights as national Nigerian filmmakers, taking their films only to the National Film and Video Censor’s Board, bypassing the Kano State Censorship Board altogether. Such films were often marked “not for sale in Kano” and if found in Kano state were known as “cocaine,” a dangerous product that could, as Iyan-Tama discovered, mean imprisonment for a filmmaker, even if filmmaker had advertised, as Iyan-Tama had, that the film was not for sale in Kano State. Another side effect of these actions was the loss of jobs among Kano youth. Ahmad Bifa pointed out that “the Hausa film industry helped reorient youth from being drug-users and area boys to finding jobs in the film profession. Sometimes if we needed production assistants we would take them and give them money. I can count many that the Hausa film industry helped become relevant people to society. But Abubakar Rabo made us go to Kaduna to do our shooting. So the young people of Kano lost the benefit of film in Kano, […] That’s why there are a lot of kids on Zoo Road who went back to being thugs because of lack of job opportunity.”

Ahmad Bifa, on set of the Aisha Halilu movie Armala, April 2011. (c) Carmen McCain

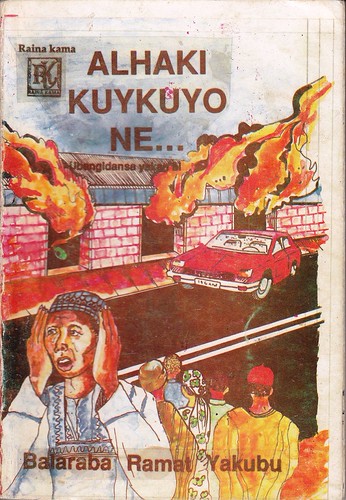

Although the impact of censorship on film was the most well known, the flourishing Hausa literary scene was also affected, with the director general initially requiring all writers to register individually with the censor’s board. With the intervention of the national president of the Association of Nigerian Authors, writers found some relief when Abubakar Rabo agreed to deal with the writer’s associations rather than with individual writers; however, there still seemed to be a requirement, at times ambiguous, that all Hausa novels sold in the state must be passed through the board. Rabo continued to make often seemingly arbitrary pronouncements about what he considered acceptable literature. In December 2009, for example, at a conference on indigenous literature in Damagaram, Niger, Rabo proclaimed that the board would not look at any more romantic novels for a year.

Abubakar Rabo Abdulkarim, DG of the Kano State Censor’s Board 2007-2011, proclaimed that he would not accept romantic novels for a year. International Conference on Authors and Researchers in Indigenous Languages, Damagaram, Niger, December 2009. (c) Carmen McCain

Those who protest the actions of the board do not have a problem with censorship so much as how censorship has been carried out. The original MOPPAN president Abdulkareem Mohammad argued that the intention of creating the censorship board had been one that would allow filmmakers to continue doing their work, “We really were doing things in good faith to ensure that things do work and eventually it is for the betterment of the majority.” He acknowledged wryly that there were flaws in the law that allowed for it to be abused, “I think that on insight, I would have done it differently.” Current president Sani Muazu continued in this vein saying that although the board had been meant to protect artists it had “become a weapon against artists.” Director Salisu T. Balarabe says, “There was nothing wrong with making the censorship board but those put in charge of directing the board, sometimes put a personal interest into it.” Novelist and scriptwriter Nazir Adam Salih acknowledged “We have our faults. This is true. But the censor’s board was much harsher than it

Novelist and script writer Nazir Adam Salih passionately responds to Abubakar Rabo Abdulkarim, at the conference in Damagaram, Niger. December 2009. (c) Carmen McCain

needed to be. They put someone in power who didn’t know anything about the film industry, Malam Abubakar Rabo, who slandered and disrespected us.” It was this disrespect and the accompanying arrests that most seemed to upset film practitioners. Danjuma Salisu, who is involved in acting, lighting, and assisting production argued that Rabo’s actions were insulting to those whose careers in film “feed our children and parents and families.” Makeup artist Husseini Tupac argued passionately, “Film is a profession. It is a career. In the same way a normal person will go to the office everyday, we will go the office, we do our work and get paid. When the honourable Dr. Rabiu Musa Kwankwaso was governor nobody ever came out on the radio and said that actresses were prostitutes, that we were making blue films, that we were rogues. No one came and arrested us.” Producer and director Salisu Umar Santa shared a similar sentiment, saying that he and other

Director Salisu Umar Santa with Dawwayya Productions, April 2011. (c) Carmen McCain

professionals he worked with, like Rukkaya Dawayya and Sadiyya Gyale, had registered and done everything the board required for working in Kano State and yet Abubakar Rabo continued to say that filmmakers were not decent members of society. Producer and Director of Photography Umar Gotip said that he felt like a refugee having to leave Kano. “You are practicing your profession, to the extent that some people even have a degree in it, but they say you are just rogues and rascals. We had no human rights.” Director Falalu Dorayi, claiming that the Kano State Censorship board regularly demanded bribes, asked “How can the one who collects a bribe say he will reform culture.” Cameraman, editor, and director Ahmad Gulu put it this way: “You should fix the leaky roof before you try to repair the floor.”

Despite his ostensible position as enforcer of public morality, Rabo himself came under suspicion of wrongdoing on several occasions. In August 2009, he was taken before a shari’a court by the Kano State Filmmakers Association and accused of slander for statements he had made about the film community on the radio. In May 2010, he was also sued in by Kaduna Filmmakers Association for accusations he had made on radio and television in Kaduna. In a strange twist, he accused twelve filmmakers, several of whom were involved the lawsuit, of sending him death threats by text message. Police from Kano came to Kaduna, arresting the one person on the list they could locate—Aliyu Gora II, the editor

Editor of Fim Magazine, Aliyu Gora II, and Filmmaker Iyan-Tama, both former inmates of Goron Dutse Prison, after a hearing in Iyan-Tama’s lawsuit against the Abubakar Rabo Abdulkarim, 22 July 2010. (c) Carmen McCain

of Fim Magazine, who was held for a week without trial at Goron Dutse Prison in Kano. In an even more bizarre twist, in September 2010, Trust and other papers reported that Rabo, after being observed late at night by police in suspicious circumstances with a young girl in his car, fled from police. In the car chase he was also reportedly involved in a hit and run incident with a motorcyclist. After he was eventually arrested and released by the police, Governor Shekarau promised to open an inquiry into the

Filmmakers on location in Northern Nigeria on Sunday, 29 August 2009, read the breaking news Sunday Trust article: “Rabo arrested for alleged sex related offence” (c) Carmen McCain

case [as requested by MOPPAN], but Rabo continued as director general of the censor’s board and filmmakers heard nothing more of the inquiry.

The treatment of filmmakers had the perhaps unintentional effect of politicizing the artists and those close to them. Sani Danja told me he had never been interested in politics until he saw the need to challenge what was going on in Kano State. A musician told me his mother never voted in elections but that she had gone out to stand in line for Kwankwaso as a protest at how her children were being treated. Filmmakers used fulsome praises to describe their delight at Kwankwaso’s

Kannywood star Sani Danja prepares for his the first press conference of his organization: Nigerian Artists in Support of Democracy (c) Carmen McCain

return. Director Falalu Dorayi said “It is as if your mother or father went on a journey and has returned with a gift for you.” Producer and director of photography Umar Gotip said Kwankwaso’s coming was “like that of an angel, bringing blessing for all those who love film.” Even those who are not fans of PDP told me they wished Kwankwaso well, were optimistic about change, and expected him to fulfill his promises in several areas: First, most of them expected that he would relieve Rabo of his post and replace him an actual filmmaker, who as Falalu Dorayi put it “knows what film is.” Secondly, several of them anticipated actual investments into the film industry “like Fashola has done for Lagos filmmakers,” as director and producer Salisu Umar Santa put it, possibly in the form of a film village. And most Kano-based filmmakers I spoke to mentioned their hopes that others who had gone into exile would come back home to Kano. Producer Zainab Ahmed Gusau, who is currently based in Abuja wrote that, “My thought is to go back to Kano, knowing there will be justice for all.We thank God for bringing Kwankwaso back to lead us.”

Hausa film producer Zainab Ahmad Gusai at the Savannah International Movie Awards, Abuja, 2010. (c) Carmen McCain

Other filmmakers saw it as a time for reflection on how they can improve the field. Director Salisu T. Balarabe mused “If you keep obsessing over what happened, the time will come and pass and you won’t have accomplished

Hausa film Director Salisu T. Balarabe on Zoo Road in the days following Kwankwaso’s win. April 2011. (c) Carmen McCain

anything. We should put aside what happened before and look for a way to move forward.” Hamisu Lamido Iyan-Tama, the politician and filmmaker who was imprisoned for three months, focused on the positive, calling on filmmakers to continue making films that would have meaning and would build up the community.

Many also looked beyond the own interests of film to the entire community.

Ahmad Gulu, Kannywood cameraman, editor, and director, on Zoo Road in the days following Kwankwaso’s win. April 2011. (c) Carmen McCain

Ahmad Gulu, cameraman, editor, and director said “The change has not come to film practitioners alone. It has come to the whole state of Kano. Back then people would accept politicians who would put something in their pockets but now things have been exposed.” Star actor, director, and producer Ali Nuhu similarly pointed out that progress was not receiving money from politicians, saying that one of the most important changes Kwankwaso could bring would be a focus on electricity, drinking water, and children’s education. Writer Nazir Adam Salih said that if Kwankwaso could simply fulfill the promises politicians and leaders had been making for the past thirty years to provide electricity and water, he will have done his job. And finally two directors of photography Umar Gotip and Felix Ebony pointed to the need for peace and unity in the state. “He should try to bring people together,” said Umar Gotip. “This kind of fighting that has arisen between Muslims and Christians is not right. We should live together as one.”

Producer Bello A. Baffancy shows off his Kwankwaso support, Zoo Road, April 2011. (c) Carmen McCain

‘Yan Fim on Zoo Road following Kwankwaso’s win, April 2011. (c) Carmen McCain