The death of Chinua Achebe has been much on my mind that past few weeks. He was one of my favourite authors and a life mentor through his writing. I plan to post some of my thoughts on him by the end of the week.

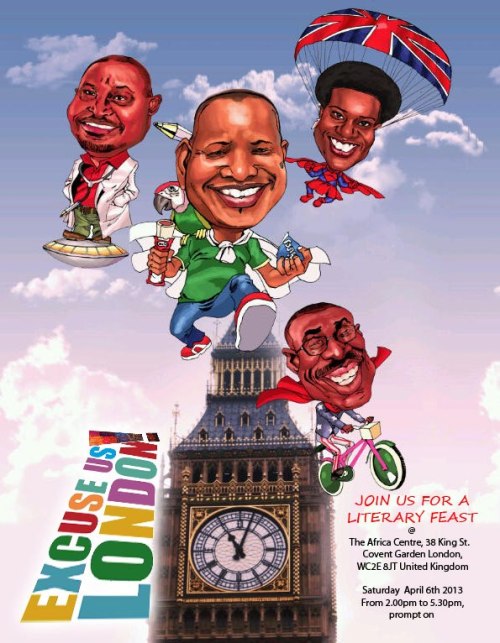

In the meantime, I wanted to post this email interview I did with Nkem Ivara, whose first novel/novella Closer than a Brother was published by Whispers Publishing on 8 March. She will be reading from the romance novel Closer than a Brother alongside artist and writer Victor Ehikhamenor, who will be reading from his nonfiction essay collectionExcuse Me!, published by Parresia Publishers, at the literary event, Excuse Us London! at The Africa Centre, 38 King Street, Covent Garden, London, Saturday, April 6, 2013, 2-5:30pm. Popular literary critic Ikhide Ikheloa and writer Ike Anya will moderate, and artist Inua Ellams will give a poetry performance. I wish I were going to be in London, as it sounds like one of the funnest literary events of the year!

(I downloaded the poster below from Facebook, where it has been making the rounds. I love it that Pa Ikhide, as we twitter groupies call him, is pictured on his keke, on which he is always *cycling slowly away*)

For a few interviews and other relevant sites for Nkem Ivara and Victor Ehikhamenor, see these links:

Victor Ehikhamenor (his website) To purchase Excuse Me!, if you are in Nigeria, you can order through Parresia or the online vendors Konga.com.ng or Jumia.com.ng. If you are outside of Nigeria, you can order it from Amazon.com

March/April 2008 Sentinel Poetry interview

27 November 2012 YNaija interview

3 January 2013 Author Q&A on Miss Ojikutu

Nkem Ivara (her blog) To purchase Closer than a Brother, you can order it online from Amazon.com or other online vendors listed at the end of the interview below.

16 November 2011, She writes the charming story of how she met her husband on Myne Whitman’s blog.

6 March 2013 JustJoxy’s review of Closer than a Brother

9 March 2013 An Interview with Myne Whitman

11 March 2013 An Interview with Kiru Taye

Here is the email interview I did with Nkem Ivara. It was originally published in Weekly Trust on 30 March 2013. Because the Weekly Trust website is having some malware issues, I’m providing a link to the interview as it appeared on AllAfrica.com.

I hope to write more about Closer than a Brother in the future and read more of the romance literature being written by Ivara’s contemporaries. I think this writing is really important, in part, because there is a huge reading public for it. Closer than a Brother already has 6 reader reviews on Amazon. When people repeat the cliche that there is no reading public in Nigeria, they don’t seem to be taking into consideration the appetite for popular literature, such as the thousands of Hausa romances and thrillers being published in northern Nigeria, or the rapidly expanding English-language Nigerian romance and erotica being made available online, whether through formally published e-novels like Closer than a Brother or informally published stories on blogs. Here is the interview. Enjoy.

Author of ‘Closer Than a Brother’

BY CARMEN MCCAIN, 30 MARCH 2013

INTERVIEW

Happy Easter! The most momentous news in world literature since I turned in last week’s column has been the passing of one of Nigeria’s greatest authors, Chinua Achebe. This week I will highlight the work of one of his literary granddaughters, London-based author Nkem Ivara, whose first novel, the 80-page Closer than a Brother was published on 8 March by Whispers Publishing. In the novel, Daye and Sami have been like brother and sister ever since 15-year-old Daye saved 12-year-old Sami from bullies. Fifteen years later in London, can Daye and Sami can make something more of their relationship without putting their long friendship at risk? Fans of romance will love the banter and sexual tension between these best friends. Will they end up together? Read to find out.Nkem Ivara agreed to an email interview for today’s column. She will read from the novel during a shared literary event with Victor Ehikhaminor at the Africa Centre in London on 6 April 2013.

Tell me a little bit about yourself and your novel Closer than a  Brother?

Brother?

I am married to a real-life drop-dead gorgeous, tall, dark and handsome hero and we have two very active boys. I enjoy playing word games, reading and hanging out with friends over a meal. I love to organise and co-ordinate events. I also enjoy watching back-to-back episodes of some American TV series e.g. Scandal, Criminal Minds, The Good Wife, Greys’ Anatomy etc.

I have been writing for a while but only started doing so seriously when I met some other writers who encouraged me to pursue it in earnest. Closer than a Brother is my first published novel. It is about best friends who fall in love but are completely unaware their feelings are mutual. Daye Thompson and Samantha Egbuson grew up in Port Harcourt, Nigeria and now live in London. Neither is willing to risk losing the friendship by revealing their true feelings. The story is told from both points of view and explores the resulting conflict and complications as they each try to conceal their feelings for the other.

When did you start writing?

Since my teens, I have dabbled in writing on and off but was reluctant to call myself a writer for fear of being asked to prove it by showing published work. That all changed a few years ago when I started writing in earnest.

What inspires you to write?

I am inspired by the world around me; and human stories of love and triumph in the face of difficulty speak to me evocatively. I love to watch people and then make up stories about them. I tend to play a game of ‘What if?’ in my head. I imagine what would happen if things went a different way. Sometimes stories are birthed from this silly exercise. For me, writing is therapeutic, it centres me and helps sort out my thought processes. It affords me the chance to let my imagination run wild.

How did the idea for this novel come to you?

I cannot remember exactly and I feel a bit like this Steve Jobs quote, “Creativity is just connecting things. When you ask creative people how they did something, they feel a little guilty because they didn’t really do it, they just saw something. It seemed obvious to them after a while. That’s because they were able to connect experiences they’ve had and synthesize new things.”

I sat down one day determined to write a story. I wanted to write something I would enjoy reading, and I have always liked the idea of best friends falling in love. I think friendship is a great foundation for building a romantic relationship. It is different from meeting someone new and trying to put your best foot forward to make yourself more appealing. The awkwardness of making new acquaintances may be absent but it presents its own set of challenges too. To fall in love with someone whose faults and foibles one is all too familiar with takes some doing. I think that is just special.

What was the process like?

The actual writing process was a lot of fun. I would write a chapter a day, and then send it to my beta-readers to critique. Beta-readers are people who read works-in-progress with the aim of improving the plot, characters, grammar etc. Their feedback was generally very positive and their suggestions helped me fine-tune the story.

Could you tell me a little bit about the Romance Writers of West Africa online community that you are a part of?

RWoWA is a support group for writers of West African origin dedicated to the growth of African romantic fiction worldwide. It was founded originally with four members, Kiru Taye, Lara Daniels, Myne Whitman and me in 2011. With the increasing demand for the African romance genre, RWoWA strives to support established and aspiring romance authors who emphasise African plot lines. All sub-categories in romance writing are covered: contemporary, historical, inspirational, paranormal and science fiction. It provides a platform for peer-to-peer critique of works-in-progress. The members have been extremely supportive by acting as beta-readers, suggesting tips and tricks to improve my work and also suggesting publishers to pitch to.

Do you write other kinds of genres, or is romance your main oeuvre?

I write whatever takes my fancy, but I am a hopeless romantic, and I do have a soft spot for romance. I write it because there is something profoundly fulfilling about the trials and triumphs of love and relationships. That whimsical combination of wistful melancholy and joyous rhapsody gets to me every time.

Could you tell me about how you found your publisher and the editing process?

Kiru Taye, a friend and founding member of RWoWA, suggested a list of publishers I should submit to. I chose four of those in addition to an African publisher. I submitted to all five according to their guidelines, and three of them responded within a few weeks. The first wanted to publish it subject to some changes of certain words and phrases like brand names etc. The second wanted to publish as it was, and the third was a very positive upbeat rejection.

I decided to go with Whispers because they liked the story exactly as it was and would only make editorial changes. The fourth publisher contacted me saying they, too, wanted to publish it but I had already signed with Whispers, so I had to turn them down.

The editing process was not as painful as I had anticipated. We had two rounds of edits. The first highlighted certain words that had occurred too often and the second was mostly getting rid of some of my 116 exclamation marks!

Any plans for future books set in Nigeria?

Yes, I have two books in the offing, both of which are set in Nigeria. One is about a married couple who have to deal with the pain and betrayal of infidelity. The other is about a couple who are manipulated into getting married.

What is your writing process like? How does your family factor into your writing?

My writing process is fluid and adaptable. As a wife and mother of two young boys, I have learned to be flexible about my schedule. I try to write everyday but I am not always successful. There are good days and some not so good days. I do not like to call them bad because though I may not actually have written anything, I am constantly thinking about the story and working on it in my head.

My husband is extremely supportive. He not only gives me room to write when I need to, but also actively encourages me to do so. I usually wait until the boys are in school or after they are in bed; it is quieter then and I can hear myself think. However, if I have a deadline, I will sometimes write to the noise of their boisterous play.

Where is the book available?

Your readers can buy my book at the Whispers Website, All Romance Ebooks, Amazon.co.uk and Amazon.com. You don’t need an e-reader to read an e-book. You can download the Kindle app to your computer, android phone, iPad etc. Readers can find me on Twitter as @thewordsmythe and my blog www.thewordsmythe.wordpress.com

A few months ago, I posted the

A few months ago, I posted the