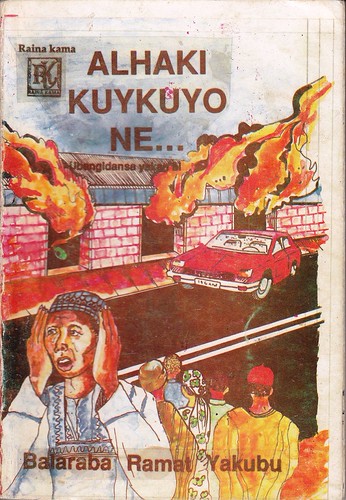

Exciting news! Indian publisher Blaft has published an English translation, by Aliyu Kamal, of Balaraba Ramat Yakubu’s 1990 novel Alhaki Kuykuyo Ne. Aliyu Kamal is a professor in the English Department at Bayero University and a prolific novelist in his own right. See Blaft’s blog post on the release, where they give this blog a shout out. Hard copies can be ordered from their site, and ebooks for Kindle and epub ($4.99) are also available. To read the first chapter for free, click here. (Update 9 November 2012: Two Indian news sites have also published articles about the novel and the influence of Indian films on Hausa culture: Dhamini Ratnam writes “Filmi Affair in Nigeria” for the Pune Mirror (and briefly quotes me) and Deepanjana Pal writes “How Bollywood fought for the Nigerian Woman “for Daily News and Analysis. I’m not sure Sin is a Puppy… is the best novel to use as evidence of Indian films on Hausa culture, but I’m delighted at the attention the novel is receiving in India.) (UPDATE 8 March 2013: You can read my review of the novel published by Weekly Trust and find links to a lot of other reviews of the novel on my blog here.)

Exciting news! Indian publisher Blaft has published an English translation, by Aliyu Kamal, of Balaraba Ramat Yakubu’s 1990 novel Alhaki Kuykuyo Ne. Aliyu Kamal is a professor in the English Department at Bayero University and a prolific novelist in his own right. See Blaft’s blog post on the release, where they give this blog a shout out. Hard copies can be ordered from their site, and ebooks for Kindle and epub ($4.99) are also available. To read the first chapter for free, click here. (Update 9 November 2012: Two Indian news sites have also published articles about the novel and the influence of Indian films on Hausa culture: Dhamini Ratnam writes “Filmi Affair in Nigeria” for the Pune Mirror (and briefly quotes me) and Deepanjana Pal writes “How Bollywood fought for the Nigerian Woman “for Daily News and Analysis. I’m not sure Sin is a Puppy… is the best novel to use as evidence of Indian films on Hausa culture, but I’m delighted at the attention the novel is receiving in India.) (UPDATE 8 March 2013: You can read my review of the novel published by Weekly Trust and find links to a lot of other reviews of the novel on my blog here.)

Hajiya Balaraba Ramat Yakubu was one of the earliest authors of what came to be known as the soyayya Hausa literary movement or Kano Market Literature. While these books were often disparaged by critics as romance novels and pulp, Hajiya Balaraba’s novels are often muck-raking exposes of abuses that occur in private domestic spaces and make a case for women’s education and independence. Other soyayya books tell love stories from the perspective of Hausa youth and tales of the home from the perspective of women.

Alhaki Kuykuyo Ne, one of Hajiya Balaraba’s most popular and critically acclaimed novels, tells the story of the family of businessman Alhaji Abdu and his longsuffering wife Rabi, the domestic fireworks that explode when he decides to marry the “old prostitute” Delu as a second wife, and the stories of his children as they make their way in the world with only the support of their mother.

When I first read the book in Hausa in 2006, I described it as follows:

Like many Hausa novels, the title is part of a proverb: “crime is like a dog”… (it follows it’s owner). When the wealthy trader Alhaji Abdu marries an “old prostitute,” as a second wife, his family goes through a crisis. After a fight between the uwargida and her children and the new wife, Alhaji Abdu kicks his first wife and her ten [nine because Alhaji Abdu kept one daughter from another marriage] children out of his house, denies them any kind of support, and refuses to even recognize any of them in chance meetings on the street or when his eldest daughter gets married. What was initially a disaster for the abandoned wife Rabi becomes a liberating self-sufficiency. Supporting her children through cooking and selling food, she is able to put her eldest son through university and see the marriage of her eldest daughter to a rich alhaji. The book follows the story of Rabi, as she makes a life apart from marriage, and her daughter Saudatu, as she enters into marriage.

I have read the translation by Aliyu Kamal and I intend to post a longer review in the next few weeks. The novel was adapted into a film Alhaki Kwikwiyo Ne directed by Abdulkareem Muhammed in 1998. Novian Whitsitt has discussed the novel in his PhD dissertation (2000), Kano Market Literature and the Construction of Hausa-Islamic Feminism: A Contrast in Feminist Perspectives of Balaraba Ramat Yakubu and Bilkisu Ahmed Funtuwa, and his article, “Islamic-Hausa Feminism and Kano Market Literature: Qur’anic Reinterpretation in the Novels of Balaraba Yakubu.” Professor Abdalla Uba Adamu has written about the screen adapatation in his book Transglobal Media Flows and African Popular Culture: Revolution and Reaction in Muslim Hausa Popular Culture and in a paper you can access online, “Private Sphere, Public Wahala: Gender and Delineation of Intimisphare in Muslim Hausa Video Films.”

As far as I know, this is the first time a full translation of a soyayya novel has been published internationally. An excerpt of Alhaki Kuykuyo Ne translated by William Burgess was published in Readings in African Popular Fiction, edited by Stephanie Newell, but Aliyu Kamal’s full translation, while it has a few issues, is much better–not quite so stiff. That is not to say there have been no other translations of Hausa literature. There are translations of the works of early authors like Abubakar Imam’s Ruwan Bagaja/The Water of Cure, Muhammadu Bello Wali’s Gandoki, the first prime minister of Nigeria Abubakar Tafawa Balewa’s Shaihu Umar, Munir Muhammad Katsin’as Zabi Naka/Make Your Choice and others. Ado Ahmad Gidan Dabino’s bestselling novel In da So da Kauna (The two part novel sold over 100,000 copies) was translated as The  Soul of My Heart, but unfortunately, although the cover illustration (pictured here) was beautiful, the translation was exceedingly bad. It cut a charming novel that was over 200 pages down to about 80, turned witty banter into cliches, and translated out most of the dialogue Gidan-Dabino is so good at. The book needs to be re-translated, this time properly. I attempted to translate Gidan Dabino’s novel Kaico!, (an excerpt of the first chapter was published by Sentinel here), but stopped because of lack of time and because I felt like my translation was still too stiff and I needed to immerse in the language a little longer before attempting more translations. As the editorial of Nigerians Talk today pointed out, we need much more focus on translation in Nigeria.

Soul of My Heart, but unfortunately, although the cover illustration (pictured here) was beautiful, the translation was exceedingly bad. It cut a charming novel that was over 200 pages down to about 80, turned witty banter into cliches, and translated out most of the dialogue Gidan-Dabino is so good at. The book needs to be re-translated, this time properly. I attempted to translate Gidan Dabino’s novel Kaico!, (an excerpt of the first chapter was published by Sentinel here), but stopped because of lack of time and because I felt like my translation was still too stiff and I needed to immerse in the language a little longer before attempting more translations. As the editorial of Nigerians Talk today pointed out, we need much more focus on translation in Nigeria.

[…] Hausa literature thrives. An old post on Jeremy Weate’s blog explores the disconnect between the idea of a thriving market selling up to “hundreds of thousands of copies” and a country that lives with a consensus that the Hausa don’t have a living literary establishment. Where are the top Hausa writers. How much of the content of their literature makes it into translation and out as a truly accessible text by other non-Hausa speakers? Where is the wall separating those work from the larger body of consumers all around Nigeria? What are the benefits and implications of this insularity that keeps a story locked only within a language medium, away from every other? And what is the value of such literature if it serves only a localized audience. What happened to universality? We won’t know any of this without active involvement of translators, and other conscious literary practitioners bringing us to the stories, and the stories to us. Like Achebe said, “my position…is that we must hear all the stories. That would be the first thing.”

I am very grateful to Blaft for initiating this translation and publication and hope that it will follow this novel with many more. The challenge will be finding translators. As I have said in a previous talk, I wish every Nigerian writer of English who spoke Hausa well would commit to translating at least one Hausa novel, so as to bring this literature to a larger public. And while I am excited that, as Blaft notes

It’s also, we believe, the first time a translation of an African-language work has ever been published first in India. We like the idea of South-South literary exchange, and we wish this sort of thing would happen more often.

I hope that some of Nigeria’s publishers will take up the challenge to create their own translation imprints.

In the meantime, a big congratulations to Hajiya Balaraba. Here’s hoping that the rest of her novels will be translated soon! Stay tuned for a longer review of

the novel itself.

For more articles and information on Hausa soyayya literature, see these links:

Interview with novelist Hajiya Balaraba Ramat Yakubu.

Interview with the first female novelist to publish a novel in Hausa, Hafsat Ahmed Abdulwahid.

Interview with novelist Bilkisu Funtua.

Interview with novelist Sa’adatu Baba Ahmed.

Hausa Popular Literature database at School of Oriental and African Studies

“Hausa Literary Movement and the 21st Century” by Yusuf Adamu

“Parallel Worlds: Reflective Womanism in Balaraba Ramat Yakubu’s Ina Son Sa Haka” by Abdalla Uba Adamu

Hausa Writers Database (in Hausa)

My blog post on a (mostly Hausa) writers conference in Niger

Pingback: Africa Blog Roundup: Piracy, Remittances, Chinua Achebe, Kenyans and Finns, and More | Sahel Blog

I am kicking myself now because I didn’t think of the title of that book by myself! It’s such a beauty!

LikeLike

Pingback: Sin is a Puppy that Follows You Home | Seema Misra

Pingback: Making History with Balaraba Ramat Yakubu’s novel Sin is a Puppy… (a review) | A Tunanina...

Pingback: Translator’s Note: Glenna Gordon’s Striking photobook Diagram of the Heart and its Many Reviews | A Tunanina...

Pingback: A Win for Translation: Fiston Mwanza Mujila’s novel Tram 83 wins Etisalat Prize for African Literature. (And I archive my articles of 2013 critiquing lack of translation) | A Tunanina...

Pingback: Hausa, una lengua africana con su propia industria cinematográfica | Literafricas