In the most recent news from Kano, singer Aminu Ala was arrested Saturday. Ala has long been known as a strong supporter of the current Kano state administration, but has recently been “on the run” since his song “Hasubanallahu” was banned by a mobile court judge linked to the censorship board. When I spoke to his contacts today about the arrest, they lamented that the song, which is written in the form of a prayer that God should punish those keeping singers from doing their work, has no bad language in it and mentions no names. According to an anonymous source, he was arrested by “workers from the Kano State Censorship Board” and detained in a police station in Sabon Gari. Eventually the same day the police were told by a superior to let him go. However, while Ala is no longer in detention, the event has increased the tension between the Kano State Censor’s Board and the entertainment industry. [UPDATE 8 July 2009: Actually what happened is that he was released on Saturday but told to show up at the Mobile Court attached to the Kano State Censorship Board at at 10am on Monday. When he did, they told him to come back at 10am Tuesday. When he and 60 other friends, supporters, and journalists showed up at 10am Tuesday, 7 July 2009, they were all told to come back at 2pm. When we came back at 2pm, he was finally read his charges–supposedly releasing his song without the approval of the censorship board. He said the charges were not true, and the prosecutor asked to reconvene on Thursday. He was denied bail until Thursday and taken to jail in a police vehicle… On Thursday he was granted bail but on the condition that he not speak to the media. See the more recent posts for the details.]

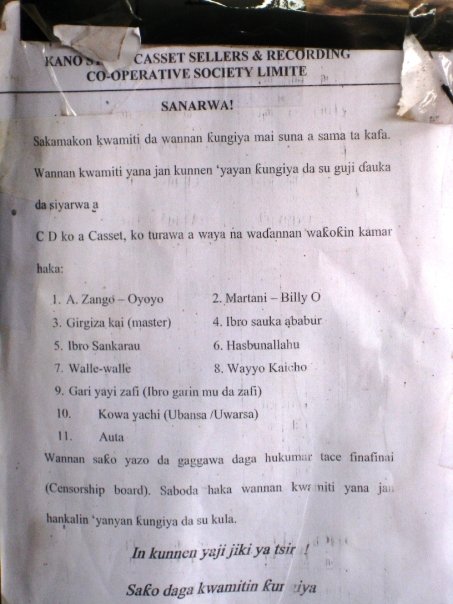

Page one of Kano State Censorship Board Press Release 3 July 2009

KSCB Press Release--3 July 2009--page 2

In the past week there has been a small war of representation going on between the DG of the Kano State Censor’s Board and the Motion Picture Practitioner’s Association of Nigeria. The DG Alhaji Abubakar Rabo Abdulkareem continues to claim that film practitioners were indisciplined and had decadent personal lives before he was appointed to lead the Censor’s Board. MOPPAN claims that Rabo’s statements are tantamount to slander of the industry, and threaten they will take him to the Islamic courts if he does not withdraw and apologize for the accusations.

Note that these accusations against the film, music, and popular literature industry are regularly made by its detractors in local media on the state radio, as well as in state-run newspapers. A few months ago there was an ad from the Kano State Censor’s Board played on state-run Radio Kano that told parents not to let their children read Hausa novels because they were spoiling their education and upbringing. I have often heard writers, filmmakers and singers lament that they do not have the resources to combat what they call “government propaganda.”

I will post below the statements that were exchanged in the past.

(Please note that these translations were done quickly and are not necessarily translated word for word, although it has been checked for accuracy by a native speaker. I take responsibility for any errors in the transcription or translation of the radio piece; however, the letters and press releases have been reproduced as released.)

On 29 June, 2009, the following short piece was broadcast on the state owned radio station, Radio Kano, in the programme, “Labarai da Rahotanni” [News and Reports]

Radio Presenter:

Ustaz Abubakar Rabo Abdulkareem yace sun sami yan fim din Hausa a zama karazube marasa tsafta. Su kuma suka ga lallai ne sai an shigar da tarbiyya da tsafta a cikin sana’ar domin ka da a lalata tarbiyya al’umar jihar nan …

Ustaz Abubakar Rabo Abdulkareem said they had found stakeholders in the Hausa film industry to be disorderly and indecent. And they [the Censor’s Board] saw the need to bring sanity and decency to the industry that is spoiling the cultural orientation of this state.

Rabo’s voice:

Mun zo mun samu bayin Allah nan, a tsari na taci barkatai. Kowa shaida ne, al’umma shaida ne. Suna cin dunduniyar juna, suna tona asirin juna, suna fada da juna, babu shugabanci, babu [bin] na gaba, babu tsari, babu doka, babu order, kai da gindi suke zaune, zaman yan marina kowa da inda ya sa gabansa. Hassali ma waccan fitana da baiwar Allan can da aka samu kowa ya gani, su suka tonawa kansu asiri a tsakaninsu mujallun da suke yi da sunan finafinan Hausa kowa in ya karanta zai ga yadda suke bayyana maganganu tsirara. Babu kara babu kawaici duk badakallar da ke tsakanin su ta shaye shayen miyagun kwayoyi suna ta neman juna maza da maza, mata da mata, za’a dauki yarinya a yi fim da ita da iznin iyayenta ba iznin iyayenta, za’a dau matar aure a shiga da ita fim ba tare da maigidanta ya sani ba sai dai in ya ganta a hoton fim irin wannan badakalar barnar da take ciki yau da muka shigo muka ce an taka birki, an hana.

We came and found that the industry was indisciplined. The evidence is everywhere. They were backbiting each other, exposing each other’s secrets, fighting with each other, no leadership, no progress, no system, no law, no order. They were self-absorbed, everyone doing what was right in their own eyes. They were exposing each other’s secrets between themselves in the Hausa film magazines. Anyone can read and see how they were directly speaking about it. No respect, no manners, taking dangerous drugs, having sex with each other, men with men, women with women. They would use a girl in a film with or without her parent’s permission, they would take a married woman and make a film with her without her husband knowing unless he saw her in the film. All of this type of spoiled and disorderly behaviour, we have arrived and we say it is prohibited, it is ended.

Radio Presenter:

Babban daraktan hukumar tace finafinan ya ce wannan ce ta sa wasu tsiraru daga cikin masu amfani da wannan mummunar hanya su nemi kudi, suke yin fada da hukumar.

The Director General of the Censor’s board said that it is because of the Borad’s actions that the minority in the industry, whose goal is only to make money, is fighting with the board.

Rabo’s voice:

Wanda yake fakewa da wannan tsari na ci barkatai yake cutar ‘ya’yan mutane ko yake samun alfanu, yau an zo an taka mar birki, me taka birkinnan ka ce Zai gan shi da haske, ka ce zai rungume shi a matsayin abokin cigaba? Ai bata taso ba.

For those who are hiding behind this indisciplined industry and are spoiling children or are profiting from it, the day has come when [these abuses] have been brought to an end. And you expect that person who has been frustrated to embrace the one who has frustrated him? Ai, that doesn’t even arise.

Radio Presenter:

Ustaz Abubakar Rabo Abdulkareem yace babu gudu babu ja da baya, hukumar za ta ci gaba da hukunta duk wani mai kunnen kashi ciki har da masu tallar magunguna mai dauke da hotunan yadda ake aikata alfasha a bainar jama’a.

Dayyabu Umar me mai rano ke dauke da Rahotan.

Ustaz Abubakar Rabo Abdulkareem says no running away, no going back, the board will continue to punish everyone who is at fault, even to those who sell medicine with pictures that will bring depravity to the community.

Dayyabu Umar brought this report.

The subsequent letter and press release from the Motion Pictures Practitioner’s Association of Nigeria [given to me in soft copy on 3 July 2009 by a member of MOPPAN. Note that I have inserted my own translation into the body of the press release, which was issued in Hausa. The letter was issued in English]:

June 30th 2009

The Director General,

Kano State Censorship Board,

Kano.

DEREGATORY RADIO STATEMENT BY DIRECTOR GENERAL, KANO STATE CENSORSHIP BOARD.

Following your radio programme titled “Labarai da Rahotanni” On the 29th day of June 2009 at Radio Kano where you defame the characters of our industry operators labelling us as lesbians and homosexuals: “Suna zama mara tsafta suna neman juna maza da maza, mata da mata.” ;a statement that no responsible government officer will dare make. We wish to draw your attention that making such derogatory and degrading remarks will not only damage the image of the film industry and its members but will also tarnish the good image of the people of Kano State at large.

2. It is against this that we demand you to withdraw your statement and apologize to the industry and its members within 48 hours otherwise we take legal action against you in accordance with the shari’a.

Mal. Sani Mu’azu

National President

cc: The Commissioner of Police,

Kano Police Command,

Bompai Kano

The Director

SSS

Kano

The Attorney General,

Commissioner of Justice,

Ministry of Justice,

Kano.

The Director

State Security Service

Kano

The Chairman,

Sharia Commission,

Kano.

The Director General

Societal Re-orientation

Kano State

The Commander General

Hisbah Board

Kano.

The Secretary

Kano Emirate Council

Kano

The Chairman

Council of Ulama

Kano

Above for your information and further necessary intervention, please.

Mal. Sani Mu’azu

National President

Press Release [from MOPPAN]

Kungiyar masu shirya finafinai ta kasa na kara bayyana damuwarta bisa kalmomin

batanci da Darakta Janar na hukumar tace finafinai da dab’i na jhar kano ke yiwa ‘ya’yanta.

[MY TRANSLATION OF PRESS RELEASE IN HAUSA]

The Motion Pictures Practitioners Association of Nigeria (MOPPAN) would like to express its dismay at the slanderous accusations against her members made by the Director General of the Kano State Censor’s Board.

Wannan ya biyo bayan hirar da aka yi da Darakta Janar a wata kafar yada labarai mallakar gwamnatin jiha a ranar litinin 29-Yuni-2009, inda ya shaidawa duniya cewa yana da tabbas bisa dabi’ar fasikanci da wai wasu masu sana’ar shirya finafinai ke aikatawa wanda ya hada da zinace-zinace da madigo da luwadi a tsakaninsu.

This follows after the interview conducted with the Director General by one of the media houses of the state government on Monday, 29 June 2009, in which he claimed to the world that stakeholders in the filmmaking profession have involved themselves into immorality such as lesbianism and homosexuality.

Sakamakon haka kungiyar na kira ga Babban Daraktan da ya janye wannan kalami na sa kana ya nemi afuwar wannan masana’anta nan da awanni 48. Rashin yin haka zai sa wannan kungiya ta kai kara gaban kotun shari’ar musulumci

Kungiyar na kuma kira gare shi da ya dubi darajar sunnan Annabi ya daina shigar da maganar Hiyana cikin maganganunsa kasancewarta yanzu matar aure ce. Wanda hakan ka iya cutar da mijinta na auren sunna.

As a result of this, the Association calls on the Director General to rescind and apologize, in the next 48 hours, for his slander against this profession. If he does not do this, this association will be forced to take him before the shari’a court. The association also calls on him to value the teachings of the Prophet and resist from involving discussions of Hiyana in his speeches since she is now a married woman. Talking thus may harm her husband and the reputation of their marriage.

Har ila yau muna kara kira ga hukumomin shari’a da hisbah na jihar kano da su jawo hankalin babban daraktan da ya kiyaye harshensa yayin da yake magana kamar yadda shari’ar musulunci ta yi umarni.

Finally, we call on the shari’a implementation agencies in Kano state to hold the Director General accountable for making sure his language is in keeping with the guidelines as established by shari’a.

Sani Mu’azu

President

(End letter and press release)

In response to the letter and press release issued by MOPPAN, the Director General of the Kano State Censorship Board issued the following response on 3 July 2009. [I re-typed the press release issued by the Kano State Censorship Board, leaving in any spelling/grammatical errors made in the original. To view the original, see the posted photographs of the press release. NOTE, THE PHOTOS APPEAR NEAR THE TOP OF THE POST–I WAS HAVING TROUBLE GETTING WORDPRESS TO PLACE THEM WHERE I WANTED THEM IN THE TEXT–CM]

PRESS RELEASE-DELIVERED BY THE DIRECTOR GENERAL KANO STATE CENSORSHIP BOARD MAL. ABUBAKAR RABO ABDULKAREEM ON 03/07/2009 AT HIS OFFICE

Distinguished ladies and Gentlemen of the press

‘EMPTY THREAT’ IS HEREBY EMTED

In the name of Allah most gracious most merciful, may Allah’s mercies and blessing be upon the exalted prophet of Islam, prophet Muhammad peace be upon him his household and his companion till the dooms day.

Background: early this week in my interview with the Kano state Radio, series of issues were addressed particularly the achievements of this administration in the sanitization and standardisation of the Hausa home video practices of which some known and repeatedly historic problems of the industry were revisited for comparison but unfortunately some few questionable elements of the film makers un-equivocally and negatively lauded a particular matter just to open a new chapter for disharmony with mischieves in order to bring back the forgone battle of words between the state with its citizenry in one side and the film practioners on the other.

This address is a by product of the pressing need of the media to balance their stories and the board to have a fair right to reply on the ‘empty threat’ of those practitioners who’s future is endangered or eroded due to our sustainable sanitization exercises. These miscreants are enemies to the present peaceful atmosphere and the cotemporary achievements of the Board because they are the beneficiaries of the old age. The age of un coordinated and un-professionalized Kannywood industry.

Hitherto, this nasty development will not in any way deter the Board on its commitment to safeguard the Kano State ideals in addition to societal values because our statutory legal undertakings are not only the promulgation of state legislation but also constitutional above all holy and sacred.

Specifically, Dear press and I want remind you about an interview granted by a re-known actress and aired in the Ray Power Radio station, Kano on 18th May, 2007, where such social ills bedevilling Kannywood where addressed by the actress i.e. Farida Jalal. The interview has now become a reference not only to me only but also to the general public (find attach 15 mins oral interview of the said actress).

Moreso, additional doziers at our disposal will not in any way help the film stakeholders when released to public especially in this period where some further negative developments are continuously unveiling and circulating.

Notwithstanding continuation of the referred interview where actresses and actors revelled atrocities of their colleagues as relate to the film business. There are equally more stronger evidences, like Gwanja-Danja panel report, assorted copies of film magazines particularly those published in vernacular among others.

Furthermore, let me use this opportunities to re-iterate one of the fundamentals of this administration which is the rule of law where equality before law is necessary. Therefore, the Board is happy that constituted measures like threat to sue organisation or person(s) is welcome by our style of leadership. Even though the Board will not hesitate to table publically at the right time and at the right place all at its possession out of social responsibilities and trust but with no meaning to join issues or make filmmakers vulnerable. Let me at this juncture warn that: “Kada Dan Akuya yaje Barbara ya dawo da ciki”. [MY TRANSLATION—CM: A male goat should not go to a female goat and return pregnant…]

In conclusion, the Board is appealing to the general public to please keep watch of their wards as relates to film industry and the rest of the popular cultural creative industries and make very good sense of judgement not only in the area of film categorisation and timing but in its entirety.

Finally, the Board is using this medium to invite you members of the media to attend the opening ceremony of a six days training-workshop on Monday 6th July, 2009 by 10:00 am at APCON lecture theatre along Kano Eastern by pass.

SIGN: MANAGEMENT